From Volkswagen’s DieselGate to Wells Fargo’s banking scandal,[1] the breadth and nature of high-profile corporate[2] and government[3] scandals and well-publicized corruption is staggering. Headlines aside, ethical misconduct is hardly uncommon today – nearly half of all fraud cases are not publicly reported[4] and over 40% of executives surveyed in a recent study said “they could justify unethical behaviour to meet financial targets”.[5]

‘Maybe someone dies’: Facebook VP justified bullying, terrorism as costs of network’s ‘growth’.

– Washington Post headline, March 30, 2018[6]

Malfeasance and unethical behaviour remains deeply entrenched in business.[7] The pervasive cheating, misconduct, and unethical behavior – and the apparent normalization of this corporate deviance[8] – has led to an increasing demand by the public for not only accountability, but also improvement in the standards of ethical behaviour, both in business and public life.

Corporate misconduct is no longer limited to just impacting the applicable individual or organization itself (if it ever was), but has significant ramifications to the economy and society – adding to people’s fears and fueling distrust in business and our institutions nationally and around the world.[9] John Shipton (chairman of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission) recently warned that a widening “trust deficit” poses catastrophic risks to the financial system.[10]

Just about every day there is a new case of corporate malfeasance—bribery, tax evasion, price-fixing, defrauding of government or consumers, environmental violations, unfair labor practices and much more. Given the frequency of these scandals, it is difficult to keep track of which corporation has done what.

– Corporate Research Project[11]

The number of headline grabbing scandals[12] that have damaged or cratered organizations, reputations, and careers – across disparate business sectors and industries – illustrate the importance of a robust corporate culture and integrity in corporate leadership. They provide important lessons[13] for corporate and government leaders – and if the opportunity is not permitted to slip away into history, may offer a roadmap for organizations going forward:[14]

“The common lesson from these scandals is that capitalism is neither inherently good nor inherently evil. But unless they are rooted out, poor cultures that permit bad individual behaviour can and will develop in businesses. … What’s critical is whether company cultures root out these bad apples, or whether they allow them to set in train a corporate race to the bottom. …

[T]here are no easy solutions. There is a consensus that regulators need to focus more on firm cultures, but little understanding about what an effective approach might look like. Greater personal liability undoubtedly has a role to play, but is no magic fix, as poor organisational cultures can encourage people to take risks regardless of the consequences.”

Unethical corporate conduct and practices carry an enormous price tag for business and society (political, economic, and social systems[15]) that requires an important level of accountability and leadership from the C-suite and of the Board of Directors. There are no shortcuts to rebuilding trust, leadership, and most importantly, a culture of integrity.

The uncertainty of the moment is palpable. Financial cleverness, platitudes, and endearing advertising is not a substitute for responsible corporate leadership and integrity.

Organizations do not transform unless people at the top of organisation adopt new values and change their behavior. The organisational culture reflects the personality of the current leadership and the legacy of personalities of its previous leaders.

– Richard Barrett[16]

Overview

Corporate misconduct indeed defies an easy solution. With respect to financial institutions alone, hundreds of billions of dollars “in fines related to misconduct have been levied” since the 2008 global financial crisis. The fact that over half of the world’s “global systemically important banks have had such misconduct-related fines levied against them, demonstrates that misconduct is not limited to just a few bad apples”.[17]

Business misconduct has grown in notoriety to such an extent that PwC has now begun measuring this threat as an independent category. For companies that have experienced fraud in the last two years, 28% confirmed they had suffered from “business misconduct” – the “risk that employee actions will imperil the delivery of fair customer outcomes or market integrity”.[18]

PwC’s 2018 fraud survey noted that 52% of economic crime was committed by internal personnel, with “a dramatic increase in the proportion of those crimes attributed to senior management”.[19]

24% of reported internal frauds were committed by senior management.

– PwC’s Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey 2018[20]

As reports of corporate misconduct, such as the ‘DieselGate’ scandal at Volkswagen[21] or the recent Commonwealth Bank scandal in Australia,[22] continue to make headlines across the globe, it is clear that the issue of unethical behavior, systemic non-compliance, and illegal conduct in corporations persists, bringing with it significant costs for businesses, customers, and society.[23] It has caused substantial financial and reputational damage to the impacted organizations themselves, but they have also caused collateral damage of billions of dollars in eroded shareholder value, financial damage to third parties, and in a number of cases bankrupt or collapsed corporations leading to thousands of lost jobs and billions of dollars of lost employee pensions. The global financial crisis of 2008 alone cascaded into a global financial meltdown that significantly threatened global capitalism, requiring “massive government bailouts and emergency stimulus programs” to “stabilize the system” – but “only after many lost their jobs and wellbeing”.[24] Although many companies paid large fines and settlements in respect to the global financial crisis, few were charged criminally, even in instances where unethical and illegal activity was widespread and well documented.[25]

Eighty-three percent of respondents agree that prosecuting individual executives will help deter fraud, bribery and corruption.

– EY 14th Global Fraud Survey: Corporate misconduct — individual consequences[26]

The rules of the game are changing profoundly and irreversibly. And frankly, better government regulation and enforcement should be part of the answer[27] to deal with global companies and large financial institutions “who dangerously go their own way”[28] – in particular consistent personal accountability of senior corporate leadership (C-suite executives and Board members)[29] as opposed to just the corporation or non-executive employees.[30] When corporate executives and board members are not consistently held accountable for corporate malfeasance – or their failure to reasonably exercise their corporate responsibility to prevent corporate misconduct – “it perpetuates the perverse incentives” that arise when executives receive compensation based on the profits of the company’s illegal activities, but the penalties for the illegal conduct are subsequently paid by the company itself (and its shareholders).[31] This “reality is most dramatically demonstrated when, as has often been the case”, even significant criminal or civil enforcement does “not result in a change in company leadership or even a measureable decrease in executive compensation”.[32]

The challenge of holding the appropriate senior leadership responsible for corporate malfeasance is not a new one,[33] however, the likelihood of significant improvement in the current political climate,[34] the push for deregulation,[35] and powerful corporate lobbying[36] is unlikely.[37]

All of the executives who met with Mr. Kushner [the U.S. President’s son-in-law and senior advisor] have lots to gain or lose in Washington. … Citigroup, one of the country’s largest banks, is heavily regulated by federal agencies and, like other financial companies, is trying to get the government to relax its oversight of the industry.

– Kushner’s Family Business Received Loans after White House Meetings, New York Times, February 28, 2018[38]

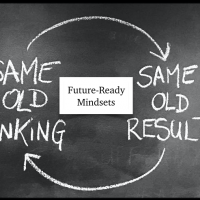

But regulation is not the sole or complete answer in any event, as companies like Wells Fargo, Volkswagen, and Enron were caught intentionally violating clear laws, as well as their own established internal compliance and ethics programs. If the leadership and culture of the organization does not support principled performance, then all of the laws and regulations – and all of the corporation’s internal written policies and procedures, people, processes, and technologies – that are put in place to mitigate ethics and compliance risks will not be effective.[39] The concerns we continue to see in respect to corporate misconduct may be due to the fact that many companies see compliance as a strict governance model and legal exercise (i.e. a “governance, risk and compliance” mindset), whereas it is really much more about behavioral science (i.e. a “governance, culture and leadership” mindset).[40] While organizations must protect themselves and their stakeholders[41] by making sure that their controls and compliance programs are truly world-class,[42] this can only be part of the solution.

Although it is important to keep companies honest by monitoring their behaviour, it is not possible for enforcement authorities or internal compliance departments to oversee all the actions of multi-national corporations at all times:[43]

“How would a global company build a big enough bureaucracy to ensure that all 100,000 employees in its operating companies worldwide follow each and every law and regulation? Even further, how could the CEO of that company be assured that his or her people were acting according to the even higher standard of behavior demanded by its stakeholder community? The answer? They can’t. Even if this company were 99.9 percent successful in its compliance efforts, that’s still 100 instances of non-compliance every day…. This is the moment to rethink how we operate, how we govern, how we lead and how we relate to society.”

Ultimately, neither external government regulation nor internal corporate compliance programs will be effective unless Board and executive leadership foster a shared corporate culture around ethical conduct that encourages employees to comply with the law and wider social expectations. Ethical leadership and culture are the two biggest determinants of how employees behave, and must be the core element of any compliance program. The comprehensive answer is for companies to develop sustainable cultures of integrity that empower personnel at all levels of the organization to make the right decisions in light of whether it is right, legal, and fair.[44]

Trust is … a critical factor of companies’ license to operate and is increasingly on the attention of business leaders.

– Rob Peters, Standard of Trust Leadership: A Clear Business Case for Trust[45]

Broad scope trust of our institutions (business and government, the economy, and yes, even the media[46]) is substantially compromised[47] by corporate misconduct tied to a desire to gain a competitive or financial advantage. The breakdown in public confidence creates risks not only for individual companies, but also our political, economic, and social systems at home and abroad.[48] PwC’s 2018 Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey underscores this theme: in it, CEOs cite trust and leadership accountability as two of the most significant threats to business.[49] Ultimately, if the foundation of a corporate organization is being undermined – or perceived to be – then how can leadership build a strong and sustainable company.

These are significant consequences. The scale of these national and international repercussions illustrate why integrity, trust, and ethical behaviour are not abstract, academic, or immaterial.[50]

[U]nlike operational breakdowns or external threats (which can often be checked by internal controls), Conduct Risk requires a more holistic response – and a shift in attitude.

– PwC’s Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey 2018[51]

Fraud and Corporate Executives

There are a number of drivers and root causes[52] that may lead to ethical misconduct and poor behaviour or practices within a particular organization (i.e. problematic corporate culture and leadership,[53] ‘profitability’ and/or ‘growth at all costs’ business model;[54] inappropriate financial/compensation goals or incentives,[55] lack of accountability, etc.), and these themes cuts across businesses, industries, and sectors.

How an individual is incentivized, evaluated and compensated … tend to focus attention on maximizing short-term profit and crowd out other important concerns about longer-term value generation, needs of customers, and broader market integrity and ethics.

– Deloitte, Managing Conduct Risk[56]

Business and government leaders are role models, whether we like it or not.[57] The success (or failure) of an overall culture of integrity begins with the leaders – the Board, the CEO, and the C-Suite executive team – and the tone they set at the top.[58] A leader’s character and behaviour shapes the culture of his or her organization and also of public opinion about an organization. And research confirms that integrity is the most important character strength for the performance and effectiveness of top-level leaders.[59]

Leadership and ethics is an imperative today: ethical behaviour must be exemplified and modeled by the leader,[60] and this includes the Board and executive leadership team. EY’s 2016 global survey found that a significant minority of executives continue to justify unethical acts to improve a company’s performance. More than one-third would be willing to justify inappropriate conduct in an economic downturn, while almost half would justify such conduct to meet financial targets.[61] In addition, studies have shown that “giving people specific, challenging performance goals” linked to compensation may have the unintended consequence of increasing their likelihood “to cheat on tasks or misrepresent their performance”.[62] In this light, we can see how the scandals at Kobe Steel, Wells Fargo and Volkswagen may well have started among a relatively small number of personnel “afraid to admit to feared top executives that they couldn’t reconcile the company’s goals and the law’s demands”.[63] The culture at Wells Fargo has been described as a toxic “soul-crushing culture of fear and intimidation” to reach extreme sales goals,[64] and Volkswagen’s has been reported to be “ruthless” – mandating “success at all costs”.[65]

This age of disruption and loss of trust – and the threat posed by even more competition and disruption on the horizon – create real, genuine pressures, and even inappropriate incentives, within an organization that may undermine ethics. It would be “nice to think” that no CEO or executive ever felt afraid or vulnerable; that all Boards can maintain their professionalism and objectivity; that all C-Suite executives can resist the “forces of short-termism” (quarterly capitalism)[66] and/or the temptation of overly risky behaviour, of cutting corners, rationalizing the bending of rules, or even participating in malfeasance. But, unfortunately, this is not the case, with “nearly three-quarters of business leaders” admitting to have taken “a professional decision that was at odds with their own ethical principles because of business pressures”.[67]

Corporate culture is widely noted as a significant root cause of the major conduct failings that have occurred across the world in recent history, causing harm to both consumers and markets. Across businesses and sectors “malfeasance remains deeply entrenched in private enterprises today”, reflecting a corporate culture in crisis and in critical need of evolution:[68]

“Millions of fraudulent accounts at Wells Fargo. Systemic deception by Volkswagen about its vehicles/emission levels. Widespread bribery at Petrobras that damaged both the government and the economy of Brazil. While those corporate scandals made headlines in recent years, countless others failed to penetrate the global consciousness. According to the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, almost half of all fraud cases are never reported publicly, and a typical organization loses close to $3 million in annual revenue to fraud. Furthermore, of the nearly 3,000 executives interviewed for EY’s 2016 Global Fraud Survey, 42% said they could justify unethical behavior to meet financial targets.”

Workplace cheating takes two major forms. First is old-fashioned lying and deception. Numbers can be altered to produce desired results. This is sometimes referred to as “cooking the books.” Done on a large scale on important documents, this constitutes criminal fraud. Done daily on internal reports it is merely “telling the boss what he wants to hear” or “getting by” or “the system.” A second way of cheating is subtle. It involves “beating the system” by manipulating what is counted in a way that produces the illusion of success but actually masks more relevant measures of performance.

– Josephson Institute’s Exemplary Leadership & Business Ethics[69]

There are many reasons for this, but one factor may be that the basic training that future business leaders receive appears to be directed to the needs of Wall Street instead of Main Street. For example, “with very few exceptions, MBA education today is basically an education in finance, not business—a major distinction”. According to business commentators such as Rana Foroohar, this influences business leaders to make “finance-friendly decisions”, and fails to provide these future business leaders with the tools and wherewithal “to cope with a fast-changing world”, or “stand up to the Street and put the long-term health of their company (not to mention their customers) first; they churn out followers who learn how to run firms by the numbers”:[70]

“[A]nyone can teach you how to read a P&L [profit-and-loss statement] or value a derivative; those kinds of things have become commoditized. The bigger challenge is to teach America’s future business leaders how to be curious, humane, and moral; how to think outside the box … [a]nd how to be strong enough to stand up to Wall Street when it demands the opposite.

…

The bottom line, though, is that far from empowering business, [in many cases the][71] MBA education has fostered the sort of short-term, balance-sheet-oriented thinking that is threatening the economic competitiveness of the country as a whole. If you wonder why most businesses still think of shareholders as their main priority or treat skilled labor as a cost rather than an asset—or why 80 percent of CEOs surveyed in one study said they’d pass up making an investment that would fuel a decade’s worth of innovation if it meant they’d miss a quarter of earnings results— it’s because that’s exactly what they are being educated to do.”

Fortune 500 company General Electric and its executives may fall into this example. GE has always been viewed as a blue chip global conglomerate. However, as we know, in 2009 the Securities and Exchange Commission investigated GE for manipulating its earnings and ultimately fined GE US$50 million for fraud. Today, in 2018, GE is again being investigated by the SEC for revenue recognition and controls, and manipulating its earnings:[72]

“There is an old joke about an executive looking to hire a new accountant. He asks each candidate: “What is one plus one?” The winner answers: “What do you want it to be?”…

Accounting fraud goes to the heart of the markets. Investors rely on financial statements to assess the future prospects of a company and expect one plus one will equal two. Any indication that the numbers were fudged puts at risk the trust investors have in management, further damaging an enterprise like G.E. that is already dealing with a host of challenges.”

Particularly telling: of the nearly 3,000 executives interviewed for EY’s Global Fraud Survey,[73] 42% said they could justify unethical behavior to meet financial targets. This must be seen as deeply concerning for Boards, governments, corporate stakeholders, and policymakers – eroding reputation and brand, and public trust in corporations and their leadership, and potentially threatening corporate sustainability and the economy.

The crisis of trust and leadership can be reasonably and credibly addressed. But is it too late? Have people now reached the point that they are skeptical that anyone can actually be an ethical leader?

A federal agency has stripped away any remaining pretense that banks are trustworthy providers of advice, assistance, guidance, help or anything else along those lines. The Financial Consumer Agency of Canada said in a report … that the corporate culture at the Big Six banks is sharply focused on selling products and services, and that there are insufficient controls in place to protect clients from aggressive sales practices. … To address this, the FCAC recommends that banks take steps like prioritizing consumer protection, fairness and product suitability … and tying employee incentives to the best interests of customers.

– Globe and Mail: The Big Six banks will fleece you – if you let them[74]

Why Do People Cheat – the normalization of cheating and deviation

To address the cause of corporate misconduct and cheating, one has to understand the cause. What drives this problem?

There is of course the “powerful forces of short-termism” afflicting corporate behaviour – discussed in an article in the Sigurdson Post last month[75] – but, for the purposes of this discussion we will discuss in more detail the “powerful psychological forces behind rule-breaking for financial gain”,[76] and a number of dynamics that foster cheating: ethical fading, ethical rationalization and ethical numbing. Fading, for example, is a process in which ethical consequences recede from awareness, and it is aided by euphemisms (i.e. “aggressive” accounting practices, as opposed to “evading taxes”).[77] Although we know quite a lot about the dynamics that people engage in to cheat – and yes, there are certainly ways to reduce and address the temptation – it is fair to say that “we are not quite as good yet about effective interventions”.[78]

Depressingly, [behavioural economist Dr. Dan] Ariely’s research[79] evidenced that the vast majority of us cheat when we think we can get away with it and that we seem to have little difficulty finding rationalizations to support our misdeeds. Moreover, the prevalence of cheating increases significantly when the cheater is part of our own social group (like a work colleague) and is further heightened if the cheater is an authority figure. [Dr.] Ariely also discovered that cheating behaviors spread like a virus from one person to another.

– Some Reflections on Cheating in Business, Corporate Compliance Insights[80]

Cheating, misconduct, deception and other forms of unethical behavior appear to be more widespread in recent years[81] – not just in business, but in sports,[82] government, schools, and many other arenas:[83]

“Cheating is deeply embedded in everyday life. Costs attributable to its most common forms total close to a trillion dollars annually in the United States alone. Part of the problem is that many individuals fail to see such behavior as a problem. “Everyone does it” is a common rationalization and one that comes uncomfortably close to the truth. That perception is also self-perpetuating. The more that individuals believe that cheating is widespread, the easier it becomes to justify. That is how cultures of dishonesty take root.

The recent election of Donald Trump is a case study in Americans’ indifference to cheating. A steady drumbeat of disclosures about fraud, illegal self-dealing, and stiffing contractors by Trump organizations did little to dislodge his support. After his election, Trump paid $25 million to settle some of the most notorious claims that Trump University had cheated its students and misled them about his own involvement in its instruction. Only a third of Americans thought he was honest and trustworthy. Close to 63 million voted for him anyway.

Whether or not Americans are cheating more, they appear to be worrying about it less.”

Large-scale unethical sales practices often begin with minor ethical compromises. Things escalate and spread from there. … As soon as the account manager gets away with the first unethical act, it’s not a big step to the fraudulent ones. The justification moves from “it’s legal” to “no one is harmed” to “no one will notice.” When such practices are tolerated, they escalate in severity and spread throughout the organization.

– Wells Fargo and the Slippery Slope of Sales Incentives[84]

With respect to business, a company’s culture is learned behaviour – a by-product of the decisions it makes or fails to make. Ethical awareness is affected by both norms and consequences: people respond to cues from colleagues, peers, and – in particular – it’s leaders (i.e. observing unethical behaviour promotes similar conduct):[85]

“Between a third to half of employees report observing workplace misconduct, and aImost half acknowledge misstatements on tax returns. In the United States alone … costs attributable to the most common forms of cheating total close to a trillion dollars annually. There is no reason to believe that the price elsewhere is any less staggering. Nor are the costs simply financial.

When manufacturers cut corners on car safety tests costs the price is paid in human lives. Honest students and athletes lose out when cheating creates an uneven playing field.

Part of the problem is that when cheating becomes pervasive, it no longer looks like a problem, or one that we are responsible for perpetuating. Many people believe that if “everybody does it,” they would be a chump not to follow suit. But that mindset creates a corrosive culture. Most of us depend for effective and efficient daily interactions on a basic level of trust.

Free markets and democratic institutions require some confidence in the integrity and fairness of others. Relatively little everyday cheating can be justified under a standard consistent with most ethical frameworks. …

In accounting for our pervasive problems with cheating, researchers emphasize the social norms, peer behavior, and rewards and penalties applicable in particular contexts. … Psychologists [have found] a number of dynamics that foster cheating: ethical fading, ethical rationalization and ethical numbing.

- Fading is a process in which ethical consequences recede from awareness, and it is aided by euphemisms. So, for example, cheaters speak of “aggressive” accounting practices, not evading taxes, and “sharing” music files, not stealing musicians’ work.

- People also rationalize their misconduct; embezzlers see their theft of funds as a form of “borrowing.” White collar offenders rarely see themselves as the kind of people who would engage in fraud; “They are victims of their own self-deception.”

- Repeated exposure to ethical misconduct can produce a form of “ethical numbing.” The more that people see others cheat, the less they regard it as cheating. And the more that they follow suit, the less discomfort they feel.

That’s how cheating cultures take root. The normalization of cheating is often so gradual that it is imperceptible. People cross the line through a series of decisions without the benefit of thorough deliberation. … Small incremental acts of cheating enable people to engage in behavior contrary to their own values without awareness that they are doing so.

Ethical awareness is also affected by both social norms and social consequences. People respond to cues from colleagues, peers and leaders, and observing moral or immoral behavior by others promotes similar conduct.”

To prevent that, the sales culture has to stop the first level of compromise, because the slippery slope begins there. As Wells Fargo has discovered in the last five years, even a strong compliance function — one that began firing people in 2011 — can’t counteract a compromised culture. When things escalate to such a scale, the problems won’t stop with salespeople. Managers and leaders may be looking the other way, or aiding and abetting the behaviors.

– Wells Fargo and the Slippery Slope of Sales Incentives[86]

A company’s organizational ecosystem may inadvertently create the underlying conditions that are usually present when personnel engage in unethical or illegal acts. There are a number of drivers and root causes that may lead to ethical misconduct within a particular organization, and these themes – applicable across businesses – may be summarized as follows:[87]

- Organizational and external influences. Unethical behavior may be triggered by both pressures or incentives (i.e. motive). Incentives may be financial or non-financial (i.e. bonus packages or stock options, promotion, time-off, etc.), however pressures (i.e. fear of failing to meet targets, or losing face, status, job, respect, purpose) may create larger problems, such as a culture driven by a coercive focus on short-term profit maximization or success at all cost. Executives, managers, and employees may be unwilling to admit they can’t meet performance targets, or afraid of the personal consequences if they do not (the ‘fear factor’ in workplace culture). An organization that prides itself on never missing a quarterly earnings target, for example, may inadvertently create this kind of pressure.

- Individual ethical decision making. Executives, managers and employees who break the rules generally convince themselves that their actions are justifiable (i.e. rationalization). In some cases, they may feel they have no alternative if they are to keep their job or meet their performance targets. Challenging poor behaviour and norms is hard (individuals tend to wish to conform to the group). In other cases, they convince themselves that their conduct isn’t really wrong, or that it is justified because the organization’s culture or leadership implicitly condones it (i.e. “if I’m the only one seeing or thinking this, it must be me that’s wrong”, loyalty to or trust in leaders, etc.).

- Business processes. Weak business practices or lax financial controls also create opportunities for unethical behavior.

What may be perceived as “small” ethical transgressions are particularly contagious, and “a key corollary of contagion is normalization”.[88] If the work culture is that “everybody does it” (and gets away with it / rewarded for it), they may need to follow suit. As well, a coercive “fear based” culture that enforces compliance and conformity undermines openness and collaboration, creating an environment – the corporate culture – where employees are not comfortable coming forward with legal, compliance, and ethics questions and concerns. From the executive suite to the front line, employees will fear retaliation and be “afraid to tell the truth”.[89]

Professor Roger Steare “corroborates the importance of context, noting that good people do bad things when driven by fear and pressure (both positive and negative) to conform. For example, the PPI scandal [financial institutions mis-selling payment protection insurance],[90] which has already cost billions in compensation and fines, was perpetrated by people working in a culture driven by short-term profit maximisation”.[91] The research strongly suggests that a majority of ‘good’ people will do ‘bad’ things if their group or community has a coercive culture that enforces compliance and conformity:[92]

“In other words, people of good character, working in a culture of fear, are more likely to conduct themselves badly and do the wrong thing. …

When faced with even a subtle threat to their jobs or their careers, good people can do bad things when faced with the need to comply not only with regulation, but also with what we might call ‘Rule #1: You will make the numbers… or else.’ …

In psychological terms, employees are making decisions because they’re afraid of personal consequences, and care less about other people – other stakeholders. This is why we call this the ’fear factor’ in workplace cultures.”

Few among us have never fallen to the temptation to tell a lie or commit an act of cheating, but when such behavior happens repeatedly, on a large scale and in large organizations, it speaks to a condition that has become contagious. Stephen Covey, the business leader … wrote, ‘The more people rationalize cheating, the more it becomes a culture of dishonesty. And that can become a vicious, downward cycle. Because suddenly, if everyone else is cheating, you feel a need to cheat, too’.

– Editorial[93]

But that mindset and behaviour creates a toxic culture. Free markets, democratic institutions, and companies require confidence in the integrity and fairness of others, but most importantly its leaders.

Some studies have suggested that people can generally be placed in one of three categories. Totally honest, incorruptible people constitute about 10 % of the population, and totally dishonest people who will cheat in a wide variety of situations account for about 5 %, with 85% basically honest acting within recognized norms and expectations (culture; tone from the top; leadership).[94] Nevertheless, research suggests that “one bad employee can corrupt a whole team”,[95] and the impact when that ‘bad employee’ is a senior leader (whether in business or government) is amplified:[96]

“[R]esearch on the contagiousness of employee fraud tells us that even your most honest employees become more likely to commit misconduct if they work alongside a dishonest individual. And while it would be nice to think that the honest employees would prompt the dishonest employees to better choices, that’s rarely the case.

Among co-workers, it appears easier to learn bad behavior than good.

For managers, it is important to realize that the costs of a problematic employee go beyond the direct effects of that employee’s actions – bad behaviors of one employee spill over into the behaviors of other employees through peer effects. By under-appreciating these spillover effects, a few malignant employees can infect an otherwise healthy corporate culture.”

A final thought is a potential systemic issue – in particular, who is identified and hired or promoted into executive leadership positions. Based on research findings, integrity is the most important character strength for the performance of top-level executives,[97] but some organizations may take the character of leadership for granted or otherwise not address the matter. We expect good leaders to be strong in character, that is, to have integrity and a moral imperative underwrite their actions.[98] Interestingly, some research suggests that while “integrity is the most important character strength for the performance of top-level executives”, it “has less to do with the performance of middle-level managers” and this “may provide some insight into why there are ethical failures at the top of organizations”:[99]

“Job performance is a well-used proxy for promotability. Managers who perform the best in their current roles are usually the ones promoted to higher levels of management. Based on our results, middle-level managers may in fact be promoted to top-level positions with little explicit regard to their integrity as it is not as important as other factors in evaluations of their current performance. In turn, when middle managers are promoted to the C-suite, they may or may not have the integrity to perform effectively at higher levels. Because integrity hasn’t mattered to their performance up to that point, it may not be considered in the promotion decisions of middle-level managers. Organizations may be promoting people up their ranks without knowledge of a crucial character strength needed in those top-level positions. When middle-level managers get to the top of organizations, they may neither have, nor have developed, the integrity needed at the highest of leadership levels.”

Leaders can work on the front-end to communicate solid business values to employees and shareholders. If you advertise that you are trying to be ethical, you’re going to wind up hiring more ethical people. It’s kind of that field of dreams thing: if you build it, they will come.

– Mark Frame, Professor (specializing in workplace psychology)[100]

The number of high profile corporate scandals over the last two decades alone – Volkswagen’s ‘DieselGate’, Wells Fargo, Enron, Kobe Steel, etc. – have distressingly exposed widespread unethical conduct, malfeasance, fraud, conflicts-of-interest, preferential treatment, corruption, insider trading, bribes, money laundering, price fixing, concealment of evidence, and Ponzi schemes “on an unthinkable scale”.[101] In these cases the corporate leadership set the tone, the rest followed the ‘unwritten corporate culture’ and so cheating within these organizations became the norm.

The recent decision of the International Olympic Committee to ban Russia from the winter Olympics is a hopeful sign of the essential changes. Cultures of cheating can change if the public demands it. Sustaining the policies and practices that encourage integrity is a collective obligation, and one in which we all have a substantial stake.

– Professor D. Rhode, Cheating: Ethics and Law[102]

Leadership and Impact on Ethics

When a crisis or scandal unfolds, we are often quick to say that “the institution allowed it”. And yet even today some in the business, political and regulatory world – often relying on the explanation of disruptive change and upheaval in a “VUCA world”[103] – many are loath or hesitant to add the necessary phrase: “and top leaders enabled it”.[104] Key drivers behind institutional failure is disruption and upheaval, but also – and most importantly – leadership failure. The failure may be unintended (i.e. may not consider at a human level how leadership’s stated strategic intent shaped the acceptable ethical boundaries for those who must turn those intents into reality), but that doesn’t exculpate the leadership for a corporation (at the Board level, C-suite), or political and government leaders in top positions:[105]

“Consider … News Corp, where editors illegally hacked cell phones to publish private information. While an editor “pulled the trigger” to illegally hack the mobile phone … Rupert Murdoch[106] enabled the decision. He didn’t set ethical boundaries in a scoop-focused media market, and he hired executives who didn’t set policies and procedures to preclude such acts. (Indeed, he rehired an executive cleared of criminal wrongdoing, signaling that her ethical and managerial failures didn’t matter.) While mid-tier executives and engineers “pulled the trigger” to design Volkswagen engines that responded falsely to emissions tests, [Chairman of Board] Ferdinand Piech and [CEO] Martin Winterkorn’s demands of win-at-all-costs performance and the absence of appropriate procedural safeguards enabled – even encouraged – them to do so. At Wells Fargo, a culture and a warped incentive system created by top executives enabled malfeasance. That didn’t stop CEO John Stumpf from blaming employees who “didn’t get it right”, or CFO John Shrewsberry from blaming “under performers”.

Without a deeply committed and constantly consistent CEO who leads a “performance with integrity enterprise” there can never be the requisite high-integrity culture. Such a culture is based on shared principles (values, policies, and attitudes) and shared practices (norms, systems, and processes) that influence how people feel, think, and behave. This is not an add-on to the CEO’s job: it is the core of the CEO’s job.[107]

The CEO must continuously lead and manage the high-integrity culture – the culture can change very quickly if not tended consistently, or in the face of a change in leadership that impacts corporate continuity.[108]

[W]e examined peer effects in misconduct by financial advisors, focusing on mergers between financial advisory firms … We found that financial advisors are 37% more likely to commit misconduct if they encounter a new co-worker with a history of misconduct. This result implies that misconduct has a social multiplier of 1.59 – meaning that, on average, each case of misconduct results in an additional 0.59 cases of misconduct through peer effects.

– Research: How One Bad Employee Can Corrupt a Whole Team, Harvard Business Review[109]

The ‘tone at the top’ sets an organization’s guiding values and ethical climate. It is a term that is used to define leadership’s commitment towards openness, honesty, integrity, and ethical behavior. The tone at the top is set by the CEO and all levels of leadership and management, including the Board – and has a trickle-down effect on all employees of an organization. If the tone set by the CEO and executive leadership upholds honesty, integrity and ethics, people are more likely to uphold those same values. The tone set at the top forms the foundation for the organization, and determines its culture, norms, and behaviour. For example:

- Sino-Forest Corporation was once the largest forestry company listed and publicly traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange, with audited financial statements of $5.7 billion in assets and $395 million net income. The Canadian CEO was found to have engaged in fraud: abusing “his unique position” to “orchestrate an extremely large and complex fraud, resulting in the loss by Sino-Forest of billions of dollars”. The CEO and key executives had fraudulently inflated its assets and earnings – the CEO being found to have specifically “lied to the Board of Directors, the Audit Committee” and its independent auditors. The company’s collapse and bankruptcy was catastrophic. In March 2018 an Ontario Superior Court judge – in a 174 page judgment – found Sino-Forest Corp.’s co-founder and former CEO Allen Chan guilty of fraud, breach of fiduciary duty and negligence, and ordered him to pay more than $2.6 billion in damages.[110]

- For decades, the United States has held itself up as a pillar of open and ethical government. On many fronts, it has led by example, enacting and enforcing some of the world’s toughest anti-corruption and ethics statutes. It has used its reputation and economic clout to prod other countries to clean up their acts, encouraging them to pass anti-bribery and transparency laws and spending millions of dollars training foreign officials in the ways of good governance—efforts that amounted to a type of soft power, smoothing over trade relations and bolstering diplomatic ties. And investors liked the predictability of open government and honest business dealings. Yet, recent reports suggest that the United States may be currently tarnishing its squeaky-clean image – its ‘tone from the top’ appearing too many to be sending a “bad signal” in respect to convincing officials in corruption-plagued countries to have the courage to combat graft.[111]

- In the UK and the era of Brexit, according to Bloomberg’s recent reporting, not everyone in government appears to want the country’s Serious Fraud Office – which investigates and prosecutes high-level corporate crime – “to chase rich wrongdoers out of the country”. There is a reported perception that “from the perspective of Britain’s leaders”, the Serious Fraud Office’s success may be “inconvenient. Brexit talks and financial planning are not going well [Brexit is identified as economically damaging in every scenario according to internal government reports, and academic consensus],[112] and Prime Minister Theresa May” may be under a certain pressure “to maintain the U.K.’s attractiveness to international capital[113] after it finally leaves the European Union. The sudden emergence of an aggressive anticorruption agency” it is reported, may be perceived to be “unhelpful to her pitch, which is aimed at such countries as China,[114] Russia, and Saudi Arabia”, reportedly “not exactly models of financial probity”.[115]

[T]aking cues from the top, a general tendency toward poor ethics is spiraling down throughout the government.

– Matthew Yglesias, Vox[116]

Leadership and culture are the biggest determinants of how employees behave. Embedding a strong ethical culture of integrity and cultivating good conduct is the key to sustaining or building reputational capital and trust, retaining customers and their loyalty, building a sustainable business, and maintaining a competitive advantage.[117] To be successful an organization must ensure it has the “right culture, the right practices, and the right behaviours”. Effective leadership is key. Leaders drive cultures of integrity.

Avoiding further self-inflicted crises – and the human damage they cause – will require more attention to both institutional norms and ethical leadership. That responsibility ultimately lies at the very top. When a Board of Directors looks to hire a CEO, for example, they must make ethics the deal-breaking criterion.[118]

The courage to speak on moral or ethical issues, and to take an ethical position becomes a greater imperative every day. With demonstrated commitment and a sense of ethics that works full time, ethical behavior must be exemplified and modeled by the leader.

—Frances Hesselbein, former Chair, Josephson Institute of Ethics[119]

It is significant that ‘trust’ is being elevated to a C-suite leadership issue[120] by many national and multinational organizations. The sustainability and success of an organization is built off of the trust in the enterprise (by customers, employees, the general public, shareholders, creditors, suppliers, regulators, media, government, etc.).[121] The best way to acquire that trust is to demonstrate values of integrity and ethics in business practices, and incorporate these values into the core fabric of the organization. Why, because values drive behaviours, and behaviours drive outcomes[122] – in this case: “trust”[123] and “reputation”.[124]

Properly fed and nurtured by leadership, ‘tone at the top’ is the foundation upon which the culture of an enterprise is built. Ultimately, it is the glue that holds an organization – a corporation and even a nation – together.[125] Study after study have shown that ethics pays: in sustainable long term success, market share, profits, reputation, customer and employee satisfaction, and in trust.

One particular study indicated that in companies where employees reported that their leaders act with integrity (an essential component of a high-trust culture), a number of competitive advantages emerged, including: (a) higher productivity, (b) increased profitability, (c) better industrial relations, and (d) greater attraction of top job applicants.[126] High-trust companies earn customer satisfaction ratings that are 2.8 to 3.2 points higher than competitors. An increase in customer satisfaction yields about a 1.6 percent increase in returns on assets.[127] During the last 15 years, researchers have estimated that the trust premium for ethical companies – the reputational value – may conservatively range from 20 to 30 percent of stock value.[128] Accordingly, reputation is an important component of an organization’s value:[129]

“Executives and outside experts alike say a good reputation adds value to the organization, helping it secure investment capital, attract talented employees, win customers, and provide a reservoir of good will to draw on when troubles arise. … A good reputation also can serve as a firewall that limits damage when something goes wrong. When stakeholders think highly of an organization, it is more likely to receive the benefit of the doubt when addressing a controversy or crisis.”

The CEO’s reputation is inextricably linked to the reputation of a company and its value. … CEO reputation is perceived to contribute nearly half (49 percent) of a company’s reputation which, in turn, is deemed to contribute to 60 percent of a company’s market value. Clearly, a CEO’s reputation has a major impact on the bottom line.

– Leslie Gaines-Ross, Who is Responsible for Corporate Reputation?[130]

A Way Forward: a systems perspective Corporate Culture

Background: ethics and compliance programs

There are significant financial, business, and reputational repercussions to not having an appropriate ethics / anti-corruption policy and effective compliance program in place (i.e. three lines of defence governance model[131] or other appropriately robust structure,[132] etc.).[133] Compliance and ethics programs serve a critical role in helping to prevent and detect misconduct at and by organizations, and to promote ethical business environments.[134] However, while organizations must protect themselves and their stakeholders[135] by making sure that their controls and compliance programs are truly world-class,[136] this is only part of the solution. Ethical leadership and culture are the two biggest determinants of how employees behave, and must be the core element of an organization’s compliance program:[137]

“For the 21st century, in order to implement a sustainable ethics and compliance program that is truly effective in shifting behaviour and mitigating risk, corporate leadership should look at moving from a strict “governance, risk and compliance” mindset to a “governance, culture and leadership” mindset. Targeting actions that will build and maintain a values-based compliance program – as opposed to a command and control compliance program – if implemented effectively with full support of the organization, should improve compliance as a result of real, tangible and sustainable behaviour change.”

To build the agility and resilience their organization needs, companies are increasingly emphasizing a “three lines of defense” approach to risk management. This governance model defines and coordinates the roles and responsibilities related to the management and oversight of risks.

– PwC[138]

There are a number of drivers and root causes[139] that may lead to ethical misconduct and poor behaviour and practices within a particular organization, and these themes cuts across businesses, industries, and sectors. However, “corporate culture” is widely accepted as a key root cause of the major conduct failings that have occurred within the business world in recent history, causing harm to both consumers and markets. Regulators and enforcement authorities around the world are progressively of the view that an ethical and compliant business culture is one of the most important tasks for corporate Boards and C-suite executives.[140]

Understanding and addressing the particular (and overlapping) drivers of misconduct that may be applicable to a particular organization is essential in improving standards of behaviour and organizational performance, and meeting regulatory, political, and marketplace expectations. This entails first identifying the key organizational risks, and then specifically addressing the corporate culture by designing and addressing applicable and appropriate enterprise-wide programs.[141]

Not surprisingly then, organizations are using ever-more powerful technology and data analytics tools (i.e. enabling technology[142]) – real time risk intelligence gathering – to enable smart decision making and risk management, fight fraud and address compliance. And, in addition to these technology-based controls, many are also expanding whistle-blower programmes, and taking steps to keep the C-suite and their Boards in the loop.[143]

Companies can respond to these challenges by both motivating their employees to do the right thing and by leveraging technological advances to identify and detect misconduct when it is not reported. Information is the key to mitigating the risks and businesses should maximize the value they get from their data.

– EY’s EMIA Fraud Survey 2017[144]

As well, many large companies are looking at whether compliance, ethics, and enterprise risk management should continue to operate as separate functions due to a concern that the disparate parts of an organization that investigate, manage, and/or report misconduct and fraud (to the Board, C-suite, or regulators) may become disjointed:[145]

“When that happens, operational gaps can emerge and fraud can too easily be brushed under the carpet or seen as someone else’s problem – to the detriment of the overall effectiveness of fraud prevention, financial performance and regulatory outcomes.

A more innovative approach is to reframe these functions as components of Conduct Risk. It enables a company to better measure and manage compliance, ethics and risk management horizontally and embed them in its strategic decision-making process. It also means fraud and ethical breaches can be approached more dispassionately, with less emotion, as a fact of life that every organisation has to deal with. Moreover, adopting this more systemic – and realistic – stance towards Conduct Risk can enable cost efficiencies between ethics, fraud and anti-corruption compliance programmes. It is an important step in breaking down the silos between key anti-fraud functions – and pulling fraud out of the shadows.”

The most effective and long-lasting way to prevent a normalization of deviance from permeating your company … is simply to … recognize that combatting the normalization of deviance requires continuous effort. It’s not a task you can check off and then ignore.

– Resolving the Normalization of Deviance by building a Culture of Communication[146]

Corporate Leadership: C-suite and Board

Responsible executive leadership and an embedded culture of integrity is integral to an organization’s success, and a critical item on every Board’s agenda.[147] For organizations to address appropriate ethical conduct requires the collective effort of the entire enterprise, operating from the same understanding of strategy, purpose, and values.[148]

A strong CEO (and their executive leadership team) must set the proper tone, the Board must have the right balance of independence and oversight,[149] and the business must be positioned to take a thoughtful approach to risk management. The CEO is key from many perspectives as “integrity flows outward from the CEO and his or her office” in a large organization[150] – however, anything short of these three criteria (i.e., a CEO who doesn’t quite get it on culture, a board that is unbalanced, under-performing or dominated by a culturally deficient CEO, and a strategic risk posture that is overly aggressive or even reckless) will undermine the sustainability and/or promotion of an ethical culture.[151]

Perhaps the most important job CEOs — and the broader business community — can do to contribute meaningfully to social progress, as well as business results, is to commit to a common purpose, a shared set of values and behaviours, and drive them through our organisations.

– Bob Moritz, PwC global chairman[152]

Corporate Culture of Integrity

In today’s environment of disruption and upheaval, it is recommended that organizations – if they have not already done so – shift from “linear thinking about culture and conduct” to a “systems perspective”. Whereas “linear thinking” diagnoses one cause to one effect, a “systems perspective” acknowledges the whole system around the individual and the interactions and inter-dependencies between each part in the system:[153]

“The question is not whether to focus on the individual or the broader organisational system. It is about examining the influences surrounding the individual, be it peers, managers, leaders, incentives, goals etc., and how aligned these factors are. Practically, this means a whole-system approach to culture with alignment between the formal (purpose, processes, structures, systems) and informal aspects (beliefs, norms and unspoken rules) and a focus on every individual in the system (organisation).”

Companies should aim for sustainable cultures of integrity that empower personnel at all levels to make the right decisions in light of whether it is right, legal, and fair.[154] Organizations without such a culture are likely to view their ethics and compliance programs as a set of “check the-box activities”, or worse, as a roadblock to achieving their business objectives. Organizations responsible for some of the most egregious acts of malfeasance have had quite impressive, formalized ethics and compliance guidelines. The problem was that either leadership or a group of influential personnel operated outside of those guidelines[155] – the corporate culture did not support principled leadership, but rather the normalization of deviation.

By paying attention to how the environment affects our choices, people can begin to treat their ethics as a skill to develop and continue developing, even as students graduate, enter the workforce, and become executives.

– Cheating business minds: How to break the cycle[156]

The single most important force for preventing misconduct (and withstanding regulatory scrutiny) is an organization’s corporate culture. To be effective, the culture, internal policies, and ‘tone from the top’ – C-suite executives and Board members[157] – must clearly reflect the company’s values of ethics and integrity.

To reinforce those values and behaviours, the company’s organizational ecosystem must address the underlying conditions that are usually present when personnel engage in illegal or unethical acts, by (a) ensuring that the company isn’t creating pressures or incentives (i.e. motive) that influence leaders and personnel to act unethically; (b) making sure business processes and financial controls minimize opportunities for unethical or bad behavior; and (c) preventing leaders and personnel from finding ways to rationalize breaking the rules. This line of thinking borrows from the classic conception of the “fraud or Compromise triangle,” which identified three elements necessary as precursors to fraud – which in our case includes misconduct generally – as: opportunity, rationalization, and pressure/incentive (motive).[158]

In this respect, the lessons learned from scandals that trace back to the early 2000s make one thing clear, it is important for Boards, CEOs and executive leadership teams to specifically “foster psychological safety and learning” as a means for managers, supervisors and employees to “speak up, collaborate, and innovate”.[159] This is where a sound corporate culture of integrity and ethics comes into play, supporting and empowering personnel at all levels of an organization – even under the most complex and stressful situations – to speak up and/or make the right decisions in light of whether it is right, legal and fair.[160] Overall, a culture of integrity may be generally characterized by the following factors:[161]

- Organizational values: A set of clear values that, among other things, emphasizes the organization’s commitment to legal and regulatory compliance, integrity, and business ethics.

- Tone at the top: Executive leadership and senior managers across the organization encourage employees and business partners to behave legally and ethically, and in accordance with compliance and policy requirements.

- Consistency of messaging: Operational directives and business imperatives align with the messages from leadership related to ethics and compliance.

- Middle managers who carry the banner: Front-line and mid-level supervisors turn principles into practice. They often use the power of stories and symbols to promote ethical behaviors.

- Comfort speaking up: Employees across the organization are comfortable coming forward with legal, compliance, and ethics questions and concerns without fear of retaliation.

- Accountability: Senior leaders hold themselves and those reporting to them accountable for complying with the law and organizational policy, as well as adhering to shared values or organizational values.

- Recruit and Promote based on character and competence: The organization recruits and screens employees based on character, as well as competence. The on-boarding process steeps new employees in organizational values, and mentoring also reflects those values. Employees are well-treated when they leave or retire, creating colleagues for life.

- Incentives and rewards: The organization rewards and promotes people based, in part, on their adherence to ethical values. It is not only clear that good behavior is rewarded, but that bad behavior (such as achieving results regardless of method) can have negative consequences.

- Procedural justice: Internal matters are adjudicated equitably at all levels of the organization. Employees may not always agree with decisions, but they will accept them if they believe a process has been fairly administered.

Commitment from senior management and a clearly articulated policy against corruption. It all starts with tone at the top. But more than simply ‘talk-the-talk’ company leadership must ‘walk-the-walk’ and lead by example.

– The 10 Hallmarks of an Effective Compliance Program: Still the Foundation[162]

Failure to build this type of culture of integrity will see the continued erosion of trust among clients and customers, employees, the public more broadly, and government and regulatory bodies in an organization’s home country – and for multinational companies – other countries throughout the world.[163]

An organizational culture that encourages ethical conduct as well as a commitment to compliance will not happen accidentally – and no number of rules, policies, monitors, or top-down controls will suffice to shape or substitute for it. The culture of an organization is the expression of its values in action; and to be successful it is up to those who shape it, particularly its leaders:

- Leaders need to support the policies, and appropriately address identifying and sanctioning unethical behavior before it gets to a level that regulators would flag.[164]

- For business leaders to establish those policies in a culture of integrity, they need to respect the consequences themselves. To that end, some recent high-profile resignations and terminations of senior executives — for example, CEO Hiroya Kawasaki at Kobe Steel, CEO Martin Winterkorn at Volkswagen, CEO Bob Diamond at Barclays, and head of compliance David Bagley at HSBC — may possibly serve as examples to other corporate personnel that someone at the top will be held personally responsible for corporate misconduct.[165]The key however, is that these executives do not then appear to be subsequently rewarded in the form of protection from criminal proceedings,[166] or with a “big payday” such as the Wells Fargo CEO walking away with approximately $100 million even with ‘clawbacks’.[167]

Just as conduct within a firm is heavily influenced by what is seen to be rewarded, failure to penalize individuals involved, as well as managers in charge, for ethically or legally questionable behaviours supports its perpetuation and can foster a culture of impunity.

– Deloitte, Managing Conduct Risk[168]

The bottom line is this: done properly, a culture of high performance with integrity will create the fundamental trust that is essential for the sustainability of a strong business.[169] Building a company’s reputation and ensuring that trust and integrity exist requires the Board, the CEO and senior executives to set the tone and communicate a consistent message.[170] Many organizations are finding that the General Counsel (who has been trained to analyze issues legally, ethically, and objectively), is also uniquely positioned to bring additional insights – ranging from ethics, reputation, and building a culture of integrity to governance, public policy, enterprise risk, and ultimately, corporate citizenship.[171]

To measure culture, we do not attempt to assess mindsets and behaviours directly; instead we recognise that there are numerous drivers of behaviour, many of which we and firms can identify and therefore manage. As a regulator, our focus is on assessing 4 of these main drivers: a firm’s purpose, leadership, approach to rewarding and managing people, and governance arrangements.

– Financial Conduct Authority (UK)[172]

Conclusion

Unethical behaviour, illegal conduct, and corruption – in fact or perception – can weaken the foundations of a healthy company, society, or economy by degrading social norms and undermining ethics and civic virtues. As recently discussed by Professor Rhode, when cheating is rewarded and when certain segments of society are seen to play by different rules, trust will give way to cynicism, and social cohesion will fragment.[173]

Loss of trust in corporate and government leaders is concerning, and, not surprisingly, sensitivity to corporate misconduct is at an all-time high. Given the disruption, loss of trust, and enormous competitive challenges today, it is more important than ever that corporate leaders and their organizations be deliberately ethical in their thinking, their behaviour, and their corporate culture. If leadership and the culture of the organization does not support principled performance, then all of the written policies and procedures, people, processes, and technologies that are put in place to mitigate ethics and compliance risks will not be effective.[174]

‘Everyone does it.’ Everyone cheats. Cuts corners. Tells lies. Maybe it was different once. Not today. If you want to succeed in this economic climate, you simply have to make compromises. Right? Wrong!

– Winners Never Cheat: Even in Difficult Times[175]

In a world where headlines are often dominated by people who make the wrong choices, people who make the right ones can seem to be rare. Integrity and values (doing the right thing) appear at times to be taking a back seat to ‘winning’ at any cost. This is the wrong path. Leadership and corporate culture is the difference, for good and bad. Misconduct and bad behaviour do not happen in a vacuum. In most scandals, many people knew or ought to have known what was taking place – executives, lawyers, bankers, auditors, and employees. For a strong ethical organizational culture, there is a basic minimum requirement to create the right systems perspective culture to ensure people act with integrity, or at least not afraid to speak out.

Business needs a robust values-based compliance program to manage the breadth and depth of ethics and compliance risk that bears down on organizations today.[176] An ethical corporate culture is the core element of a successful compliance program – requiring a focused tone from the top and engagement of the Board. If the culture of the organization does not support principled performance, then all the other tools put in place to mitigate ethics and compliance risks will not be effective.

What in the world causes this? I doubt that the people at NASA, Ford, GM, Volkswagen, and B.F. Goodrich are inherently evil or dishonest. What convinced them to put their code of ethics on hold? According to Diane Vaughan, a sociologist, it was nothing – or at least, no one thing. Rather, Vaughan says that actions that have always been thought of as “not okay” are slowly reclassified as ‘okay’ over a period of time, through a gradual cultural shift. She calls this the Normalization of Deviance. The term, “slippery slope,” is terribly overused these days, but the Normalization of Deviance is just such a slope.

– Patrick Leach, Normalization of Deviance[177]

There are many examples of temporary winners who won by cheating. For a number of years, Enron[178] was cited as one of America’s most innovating and daring companies. The CEO of the company knew the most important people in the country, including the President of the United States. Except that Enron’s success was built on lies, and the “winners” who headed the company went to jail, the company (the sixth largest in the U.S. at the time) collapsed, and the scandal is now a case study in every business school in the world.[179]

Employees also want to see a higher standard of behavior within their organizations – they want their organizations to be more ethical.[180] Unfortunately, not all leaders are created equal.[181] It is important to understand that just because someone holds a position of leadership, does not mean they should. It doesn’t matter how intelligent, affable, persuasive, or savvy a person is, if they are prone to rationalizing unethical behavior, they will eventually fall prey to their own undoing, ultimately damaging or taking down the organization and its stakeholders with them. Optics over ethics is not a formula for success.[182]

[W]e are all confronted with ethical dilemmas … but it’s how we chose to respond to these dilemmas, that characterises whether we are real leaders or not. We may occupy leadership roles, but when we behave unethically, we cease to become leaders.

– Andrew Simon[183]

Integrity is the supreme quality of leadership[184] and the key ingredient in developing and maintaining trust.[185] Creating a winning culture founded on integrity and trust is a strategic imperative that will create, build and sustain organizational results (i.e. greater profitability, higher return on shareholder investment, decreased turnover of top performers, increased employee engagement, heightened client and customer service, increased collaboration and teamwork, higher productivity, enhanced creativity and innovation, etc.).[186] It will also make it less likely for an organization to slip into the normalization of deviance.

You will know you have the winning formula when your leadership and corporate culture provides personnel at all levels of the organization the authority, safety and support “to stand in front of the train of fast-moving” events and do the right thing.[187]

Effective leadership is key. Leaders drive cultures of integrity.

Eric Sigurdson

Endnotes:

[1] Scandals and organizational crisis that trace back to the early 2000s: Enron (2001), HIH Insurance (2001), WorldCom (2002), Freddie Mac mortgage scandal (2003), AIG accounting scandal (2005), Lehman Brothers investment bank and subprime mortgage crisis (2008), Libor (London Interbank Offered Rate) fixing scandal and Barclays Bank, Deutsche Bank, etc. (2012), General Motors’ concealment of defective ignition switches killing 13 people (2014), Petrobras multibillion dollar Brazilian money-laundering and bribery scandal (2014), Volkswagen’s DieselGate (2015), Wells Fargo banking scandal (2016), United Airlines (2017), Japan’s Kobe Steel falsified quality control data scandal (2017), as well as the 2008 credit markets’ disintegration that cascaded into the global financial meltdown that significantly threatened global capitalism. See, Chris Matthew and Matthew Heimer, The 5 Biggest Corporate Scandals of 2016, Fortune, December 28, 2016; Geoffrey James, Top 10 Brand Scandals of 2015, Inc., September 26, 2015; Syed Balkhi, 25 Biggest Corporate Scandals Ever, List25.com, July 15, 2014; Top 10 CEO Scandals, Time, August 10, 2010. Also see, Ryan Cooper, A brief history of crime, corruption, and malfeasance at American banks, The Week, October 9, 2017.

[2] For example: Matthew Miller, Canadian Court awards $2.6 billion in Sino-Forest fraud case, Reuters, March 15, 2018; Josh O’Kane, OSC rules Sino-Forest defrauded investors, misled investigators, Globe and Mail, July 14, 2017; Thomas Gryta, Joann Lublin, and David Benoit, How Jeffrey Immelt’s ‘Success Theater’ Masked the Rot at GE, Wall Street Journal, February 21, 2018; Peter Henning, Accounting Investigation Adds to Challenges Facing G.E., New York Times, February 2, 2018; Matt Egan, GE is under SEC investigation, CNN, January 24, 2018; Makini Brice and Lawrence White, Barclays to pay $2 billion fine over U.S. mortgage fraud claims, Globe & Mail, March 29, 2018; Ryan Cooper, A brief history of crime, corruption, and malfeasance at American banks, The Week, October 9, 2017; Emily Cadman, How Outrage Over Australian Banks Sparked a Public Inquiry, Bloomberg, November 30, 2017; Roger Parloff, How VW Paid $25 Billion for ‘DieselGate’ – and Got Off Easy, Fortune, February 6, 2018; Jack Ewing, Volkswagen CEO Martin Winterkorn Resigns Amid Emissions Scandal, New York Times, September 23, 2015; Katharina Bart, The Fall of Switzerland’s Uber-Banker, Finews.asia, March 2, 2018; Yeo Jiawei’s Ex-BSI Boss Describes 1MDB Kickbacks, Lavish Lifestyle, Cover-Up, Finews.asia, November 2, 2016; Sean McLain and Chieko Tsuneoka, Kobe Steel Admits 500 Companies Misled in Scandal, Wall Street Journal, October 13, 2017; Masumi Suga and Ichiro Suzuki, Kobe Steel Chief Quits as Report Finds New Misconduct Cases, Bloomberg, March 6, 2018 (“blamed on an overemphasis on profitability, poor governance”); Alan Salpeter, Emily Newhouse Dillingham, Lessons counsel should learn from the GM ignition switch failure, Inside Counsel, May 11, 2015; Matt Egan, Bank of America ‘systematically’ misled clients about stock trades, CNN, March 23, 2018; U.S. Bancorp agrees to pay $613m to resolve issues related to BSA, Anti-Money Laundering compliance, Northern Kentucky Tribune, March 4, 2018; Liz Moyer, US Bank to pay more than $600 million over federal charges it had lax anti-money laundering controls, CNBC.com, February 15, 2018; Abhirup Roy and Devidutta Tripathy, India’s PNB Bank fraud likely to swell beyond $2 billion mark, CNBC.com, March 6, 2018; Canadian Press, Sino-Forest Corp. co-founder and former CEO found guilty of fraud, Toronto Star, March 15, 2018; Tom Warren and Alex Campbell, Revealed: The Secrets of One of the World’s Dirtiest Banks and its Powerful Western Protectors, BuzzFeed News, December 13, 2017; Tom Warren and Alex Campbell, How Deutsche Bank Enabled A Dirty Offshore Bank to Move Dark Money, BuzzFeed News, December 15, 2017; Kevin McCoy, Peanut exec in salmonella case gets 28 years, USA Today, September 21, 2015; Marina Strauss, Consumer Trust in grocers tumbles after bread-price-fixing scheme: study, Globe and Mail, March 20, 2018; Deborah Rhode, Cheating: Ethics and Law in Everyday Life, Oxford University Press, October 2017; Eric Sigurdson, Corporate and Government Scandals: A Crisis in ‘Trust’ – Integrity and Leadership in the age of disruption, upheaval and globalization, Sigurdson Post, May 31, 2017; Eric Sigurdson, General Counsel and In-House Legal as Corporate Conscience: an evolutionary crossroads in the age of disruption, Sigurdson Post, June 29, 2017.

[3] For example: Jesse Drucker, Kate Kelly, and Ben Protess, Kushner’s Family Business Received Loans after White House Meetings: Apollo, the private equity firm, and Citigroup made large loans last year to the family real estate business of Jared Kushner, President Trump’s senior advisor, New York Times, February 28, 2018; Jill Abramson, Nepotism and corruption: the handmaidens of Trump’s presidency, The Guardian, March 6, 2018; Bradley Hope, Tom Wright, and Rebecca Ballhaus, Trump Ally Was in Talks to Earn Millions in Effort to End 1MDB Probe in U.S., Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2018; Arjun Kharpal, Trump ally reportedly in talks to earn $75 million is he could get the US probe into 1MDB dropped, CNBC, March 3, 2018; Pam Martens and Russ Martens, Citigroup’s Loan to Kushner: The Devil is in the Details of Citi’s Sordid History, Wall Street On Parade.com, March 1, 2018; Ralph Jennings, Bad For Business? China’s Corruption Isn’t Getting Any Better Despite Government Crackdowns, Forbes, March 15, 2018; Ferial Haffajee, Zuma’s Indictment on Corruption Sets An African Precedent: Zuma joins former Brazilian, Guatamalan and South Korean leaders in the dock for corruption this year, Huffington Post, March 16, 2018; David Frum, Can a New President Really Solve South Africa’s Corruption Problem?, The Atlantic, March 2, 2018; Andy Kroll and Russ Choma, Trump Has Turned America’s Reputation for Fighting Corruption into a Joke, Mother Jones, July-August 2017. Also see, Jesse Drucker, Kate Kelly, and Ben Protess, Kushner’s Family Business Received Loans after White House Meetings: Apollo, the private equity firm, and Citigroup made large loans last year to the family real estate business of Jared Kushner, President Trump’s senior advisor, New York Times, February 28, 2018; Jill Abramson, Nepotism and corruption: the handmaidens of Trump’s presidency, The Guardian, March 6, 2018; Nina Burleigh, Trump VS. Mueller: Is the American Legal System Any Match for the President, Newsweek, March 8, 2018; Ian Austen and Dan Bilefsky, Trump Says He Made Up Deficit Claim in Talk with Trudeau, Baffling Canadians, New York Times, March 15, 2018; Virginia Heffernan, Ivanka Trump: Born to legitimize corruption and make the shoddy look cute, Los Angeles Times, March 3, 2018; Suzi Ring and Franz Wild, Britain’s White-Collar Cops Are Getting Too Good at Their Job: In the era of Brexit, not everyone wants the Serious Fraud Office to chase rich wrongdoers out of the country, Bloomberg, March 1, 2018. Also see, Suzi Ring, SFO Stalls on Airbus Probe as U.K. Seeks Brexit Business, Bloomberg, November 14, 2017; Tom Warren and Alex Campbell, Revealed: The Secrets of One of the World’s Dirtiest Banks and its Powerful Western Protectors, BuzzFeed News, December 13, 2017; Tom Warren and Alex Campbell, Exposed: Kremlin-Linked Slush Funds Funnelling Money to Syria’s Chemical Weapons Financiers, BuzzFeed News, December 14, 2017; Tom Warren and Alex Campbell, How Deutsche Bank Enabled A Dirty Offshore Bank to Move Dark Money, BuzzFeed News, December 15, 2017; Samuel Petrequin, Suitcases full of cash? Ex-French president Sarkozy arrested as police probe allegations of illegal Gadhafi millions, National Post, March 20, 2018; Zane Schwartz, Follow the Money – why politicians may not want you to use this database, National Post (Canada); Simon Nixon, The Dark Underbelly of Europe’s Financial System: The EU has rules to guard against money laundering, but members must ensure the law is enforced, Wall Street Journal, March 14, 2018.

[4] 2016 Global Fraud Study: Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, 2016; Hui Chen and Eugene Soltes, Why Compliance Programs Fail – and How to Fix Them, Harvard Business Review, March-April 2018.